perspectives others reasons

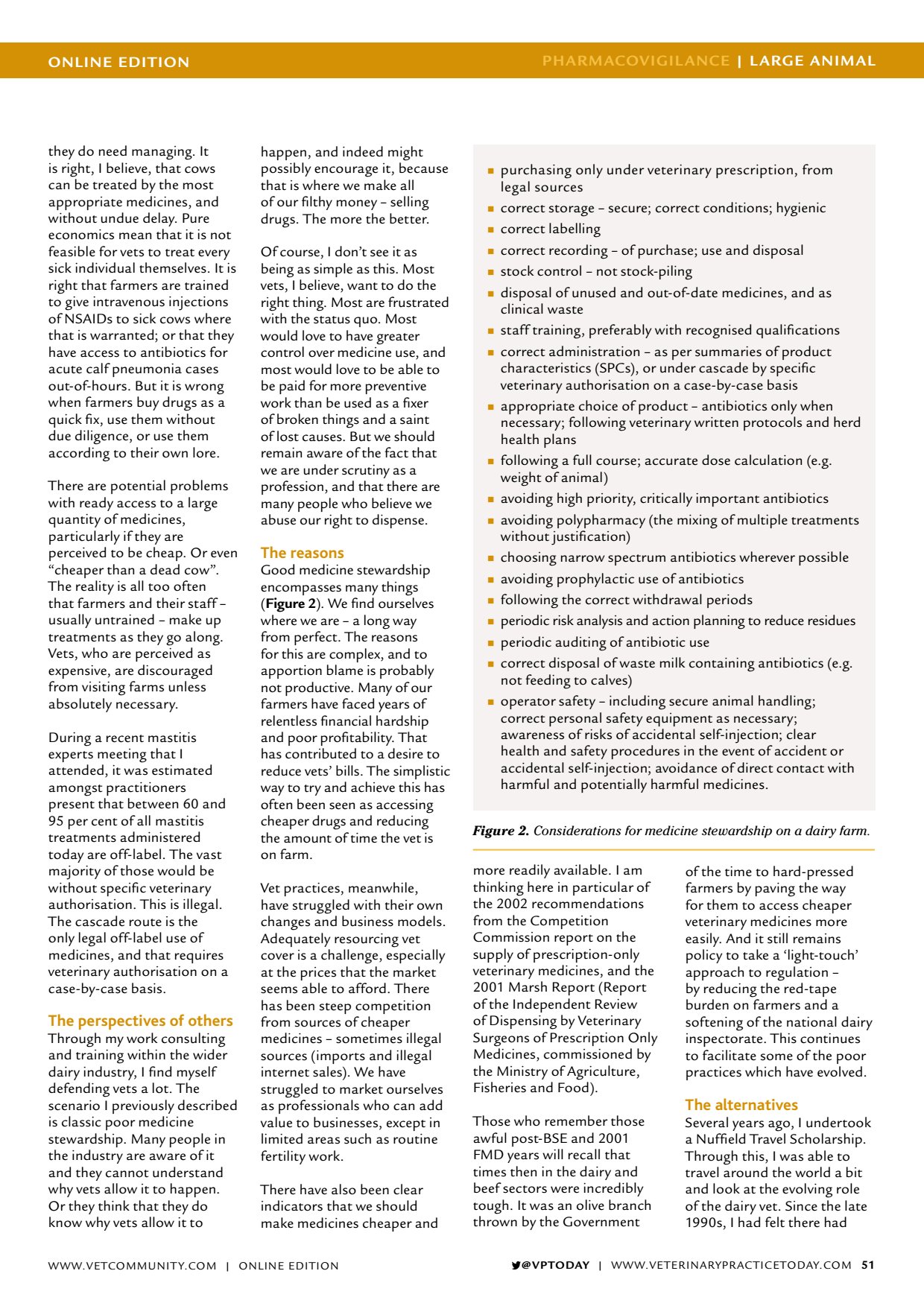

ONLINE EDITION PHARMACOVIGIL ANCE | L ARGE ANIMAL VPTODAY | WWW.VETERINARYPRACTICETODAY.COM 51 they do need managing. It is right, I believe, that cows can be treated by the most appropriate medicines, and without undue delay. Pure economics mean that it is not feasible for vets to treat every sick individual themselves. It is right that farmers are trained to give intravenous injections of NSAIDs to sick cows where that is warranted; or that they have access to antibiotics for acute calf pneumonia cases out-of-hours. But it is wrong when farmers buy drugs as a quick fix, use them without due diligence, or use them according to their own lore. There are potential problems with ready access to a large quantity of medicines, particularly if they are perceived to be cheap. Or even cheaper than a dead cow. The reality is all too often that farmers and their staff usually untrained make up treatments as they go along. Vets, who are perceived as expensive, are discouraged from visiting farms unless absolutely necessary. During a recent mastitis experts meeting that I attended, it was estimated amongst practitioners present that between 60 and 95 per cent of all mastitis treatments administered today are off-label. The vast majority of those would be without specific veterinary authorisation. This is illegal. The cascade route is the only legal off-label use of medicines, and that requires veterinary authorisation on a case-by-case basis. The perspectives of others Through my work consulting and training within the wider dairy industry, I find myself defending vets a lot. The scenario I previously described is classic poor medicine stewardship. Many people in the industry are aware of it and they cannot understand why vets allow it to happen. Or they think that they do know why vets allow it to happen, and indeed might possibly encourage it, because that is where we make all of our filthy money selling drugs. The more the better. Of course, I dont see it as being as simple as this. Most vets, I believe, want to do the right thing. Most are frustrated with the status quo. Most would love to have greater control over medicine use, and most would love to be able to be paid for more preventive work than be used as a fixer of broken things and a saint of lost causes. But we should remain aware of the fact that we are under scrutiny as a profession, and that there are many people who believe we abuse our right to dispense. The reasons Good medicine stewardship encompasses many things ( Figure 2 ). We find ourselves where we are a long way from perfect. The reasons for this are complex, and to apportion blame is probably not productive. Many of our farmers have faced years of relentless financial hardship and poor profitability. That has contributed to a desire to reduce vets bills. The simplistic way to try and achieve this has often been seen as accessing cheaper drugs and reducing the amount of time the vet is on farm. Vet practices, meanwhile, have struggled with their own changes and business models. Adequately resourcing vet cover is a challenge, especially at the prices that the market seems able to afford. There has been steep competition from sources of cheaper medicines sometimes illegal sources (imports and illegal internet sales). We have struggled to market ourselves as professionals who can add value to businesses, except in limited areas such as routine fertility work. There have also been clear indicators that we should make medicines cheaper and more readily available. I am thinking here in particular of the 2002 recommendations from the Competition Commission report on the supply of prescription-only veterinary medicines, and the 2001 Marsh Report (Report of the Independent Review of Dispensing by Veterinary Surgeons of Prescription Only Medicines, commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food). Those who remember those awful post-BSE and 2001 FMD years will recall that times then in the dairy and beef sectors were incredibly tough. It was an olive branch thrown by the Government of the time to hard-pressed farmers by paving the way for them to access cheaper veterinary medicines more easily. And it still remains policy to take a light-touch approach to regulation by reducing the red-tape burden on farmers and a softening of the national dairy inspectorate. This continues to facilitate some of the poor practices which have evolved. The alternatives Several years ago, I undertook a Nuffield Travel Scholarship. Through this, I was able to travel around the world a bit and look at the evolving role of the dairy vet. Since the late 1990s, I had felt there had purchasing only under veterinary prescription, from legal sources correct storage secure; correct conditions; hygienic correct labelling correct recording of purchase; use and disposal stock control not stock-piling disposal of unused and out-of-date medicines, and as clinical waste staff training, preferably with recognised qualifications correct administration as per summaries of product characteristics (SPCs), or under cascade by specific veterinary authorisation on a case-by-case basis appropriate choice of product antibiotics only when necessary; following veterinary written protocols and herd health plans following a full course; accurate dose calculation (e.g. weight of animal) avoiding high priority, critically important antibiotics avoiding polypharmacy (the mixing of multiple treatments without justification) choosing narrow spectrum antibiotics wherever possible avoiding prophylactic use of antibiotics following the correct withdrawal periods periodic risk analysis and action planning to reduce residues periodic auditing of antibiotic use correct disposal of waste milk containing antibiotics (e.g. not feeding to calves) operator safety including secure animal handling; correct personal safety equipment as necessary; awareness of risks of accidental self-injection; clear health and safety procedures in the event of accident or accidental self-injection; avoidance of direct contact with harmful and potentially harmful medicines. Figure 2. Considerations for medicine stewardship on a dairy farm. WWW.VETCOMMUNIT Y.COM | ONLINE EDITION